Female photographers were central to my first serious classes at university. Add to this the egalitarian nature of photographing - after all, as Chef Custeau would have said, had he been a photographer and not a chef: “Anyone can photograph." There is a level playing field for the photographer - any photographer - to create a good, or even a great image. Sure, there are lots of barriers from a work place point of view, glass ceilings, and so forth, but the image itself is available to anyone. If you could lay your hands on a camera and some film, you could create. Today the average phone can do the trick. I hope that my time spent at a feminist university, in the company of women photographers, has stood me well. I try to be humble and appreciate great work, whatever the source.

Abigail Heyman: “Confused Army” 1971

I have thought often about the days when I sat in “Women Photographers of the 20th Century” watching all those images that moved from the projector to the screen, while the talking head up front pointed out particular qualities and characteristics that were important to pass the next exam. The list of excellent female photographers; famous, well-known and less-well-known is long, impressive and growing all the time.

Personally, I am drawn to work that has an ephemeral quality, where the photographer, the printing, the paper and the image come together in splendid whole, capturing an elusive fraction of a second in time. When this is successful, there is nothing like it. You can have long discussions about the technical aspects of all the steps that go into making a great photograph, but at the end of all this, only one thing remains, the gift that the photographer presents to you, or me, the viewer.

Photographs that really work have this extra quality that you cannot put your finger on. For me it is a whole movie with a great soundtrack condensed and concentrated into a single frame on a small piece of paper, brought to life by the vision of the photographer. There need be no lengthy description, no deeply articulated justification for the work. There is the work. The single image. The story that I get to write in my mind is mine, and mine alone, as I look at this humble piece of paper with blacks, and whites and all manner of greys in-between.

I am drawn, in particular to a quote by Jürgen Schadeberg, who very smartly points out that: “there are certain moments we do not see unless we photograph them.” This goes hand-in-hand with what Edouard Boubat has said many times: “The photographer sees the same show that everyone else sees. He however stops to watch it.”

Abigail Heyman: “Houma Teenage Beauty Contest” 1971

I cannot pretend that these seemingly simple observations apply to all photography. Sometimes elaborate sets are constructed, lights are erected, timers engaged and subjects distracted by little birds on the end of a toy fishing pole to encourage that particular smile, or a whole phalanx of assistants mill about eagerly anticipating the second when the maestro will press the shutter, before moving on to the next frame. But, this is not my kind of photography. It usually doesn’t speak to me.

When I really pay attention. When I really see. There are gifts everywhere. One of my all time favourite photographs, and yes, by one of those hardcore feminist photographers, is by Abigail Heyman: “Supermarket” 1972. There is something very familiar to those of us who were around in the 1970s, who might have seen this exact scene play out any number of times, without really noticing it. But, as Boubat and Schadeberg both suggest, there is genius in stopping, watching and recording.

Abigail Heyman: “Supermarket” 1972

There is a time, a context, and a reality captured in this photograph, which on one hand is simply a 1972 snapshot at the supermarket, but there is genius in the composition, the generational play, the possibility of bleak future for the young woman in the foreground, who appears to be working on nothing more than becoming her mother, represented by the older ladies just behind her. A cycle to be repeated over, and over again. But in this photograph I see a message of hope that the cycle can be broken. The photographer uses the mundane to put forward a new idea, a new vision, and a different future. There is a streak of defiance in the young lady’s eye, and a brighter flower on her dress. By pointing to the mundane and sad mediocrity of the suburbs in 1972, a simple message is delivered. We don’t all have to become our parents. God forbid. We can break the cycle. Make our own reality. We can change the world!

Double-page spread from Abigail Heyman’s first book:

Abigail Heyman: Double page spread from “Growing up female a personal photo-journal by Abigail Heyman” - “Factory Lunch” 1973 and “August 26 Man-Children” 1971

Abigail Heyman was one of the first female photographers to join the Magnum Agency. She photographed women and women’s life. Her three books, of which the first was a sensation when first published, “Growing up female a personal photo-Journal by Abigail Heyman” (1974). The cover looks like it was written in a hurry with a soft #2 pencil:

Abigail Heyman: Book cover, 1974

This was followed by “Butcher, Baker, Cabinetmaker” (1978). A book of photographs of women at work. Her third and final book “Dreams & Schemes: Love and Marriage in Modern Times” (1987) was her photographic vision and distillation of more than 300 weddings she attended to gather material for the book.

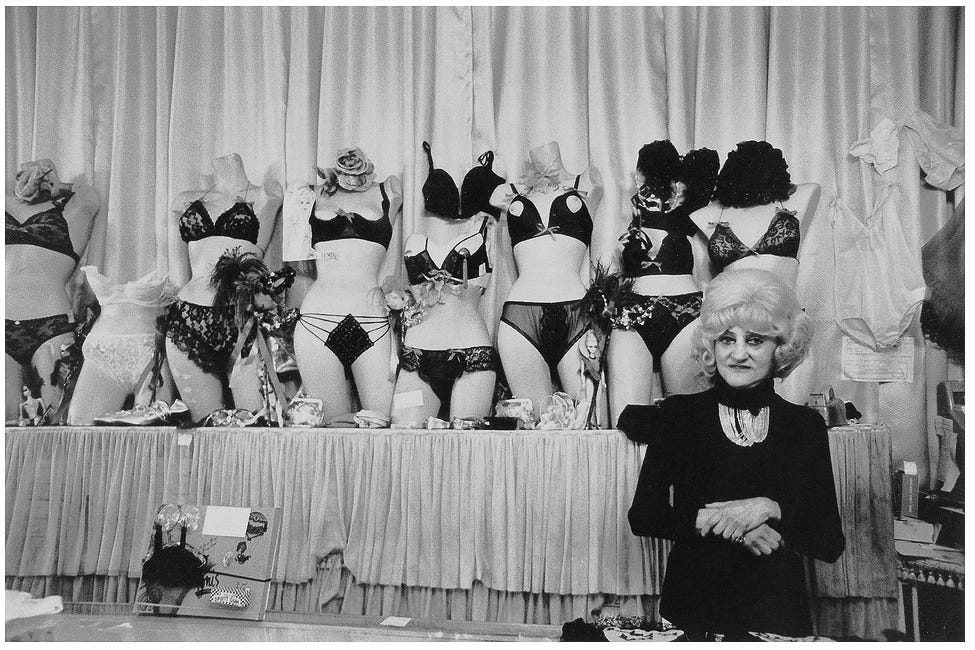

Abigail Heyman: “Lingerie Shop” 1972

Abigail Heyman lost traction along with her version of the feminist movement running out of steam. She went on to teach and work for the International Center of Photography in New York. She passed away in obscurity in 2013. She was 71.

She may have lost the spark towards the end, but her contribution to photographic excellence is not in dispute.

I appreciate it. I found Abigail by chance some years ago. I bought the photograph from the supermarket and then started looking for more of her work. She was very, very good.

love this essay, absolutely love it! especially that i never heard of abigail. well done! oh, if possible, please post more essays like this.